In today’s example, we will be demonstrating routing between host A and host B in different subnets, but within the same tenant (VRF). While routing in traditional networking is built into the DNA of network engineers, when working with overlay technologies, routing adds an interesting twist to challenge our understanding.

Opening Thoughts

My learning journey on MP-BGP EVPN VXLAN has been interesting to say the least. I’ve always used multiple materials to learn the same topic because there will be different perspective and coverage angle depending on the author. For MP-BGP EVPN VXLAN, I have used Cisco Live, Cisco press books and even configuration guides to learn. Especially for L3 overlay technologies, I have found the use of certain networking constructs confusing, such as the need to use VRF or BGP IPv4 address family, and how does it apply to our use case. I hope you will find this piece as entertaining as I have found exploring and writing the foundations of L3VNI and the supporting technologies to enable L3 overlay service.

Technically, we could configure an L3 overlay service on MP-BGP EVPN VXLAN without really understanding why certain configuration is required or how they support the entire solution. But this is not what we should do here. As much as we can, we should be responsible for every line of configuration, and understand how they fit in to the use case.

Let’s lab and learn together.

Major Questions

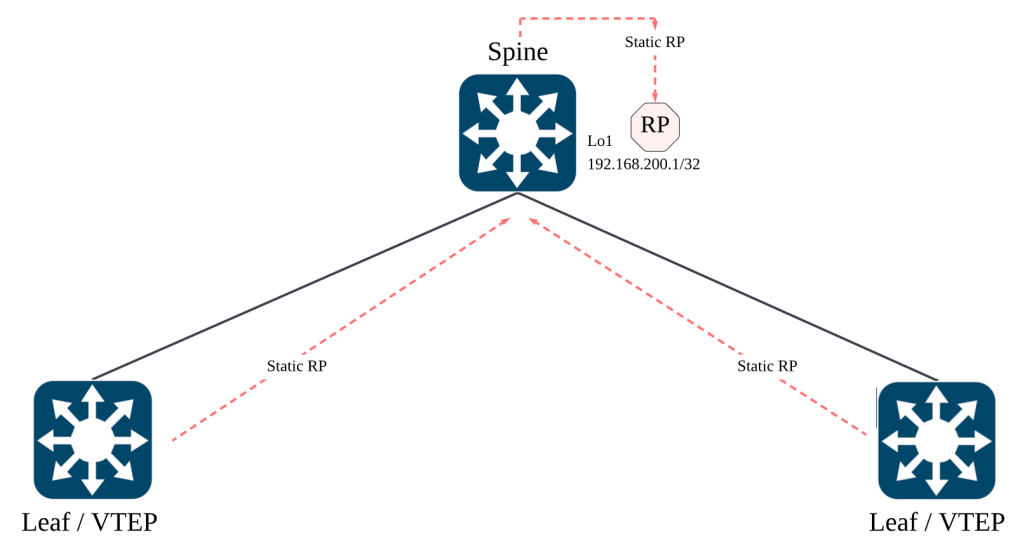

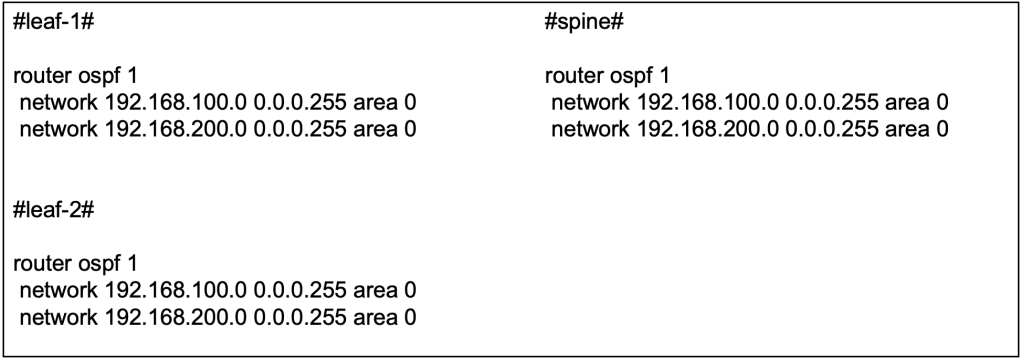

In my journey to explore L3 overlay using MP-BGP EVPN VXLAN, I found myself asking for the purpose of certain protocols that are used as building blocks for the entire solution. Referencing to Cisco Live BRKENS-3840 (Under the Hood of IOS-XE EVPN/VXLAN on Catalyst 9000) by Dmytro Vishchuk, he has brilliantly came up with a sample config, shown below.

Apart from the obvious that we need an L3VNI, associating the L3VNI to the NVE, I have found myself asking these questions, to myself.

- Why is VRF required if I do not have multiple L3VNI / L3 Overlay service?

- What is BGP IPv4 address family required when we already have EVPN address-family?

- Why do we need route target? What is stitching?

If you may have similar questions like I do, perhaps this blog post will be relevant to you.

Similarity to MPLS L3 VPN

I personally find the foundation of MPLS L3 VPN to be similar in concept to L3 overlay in MP-BGP EVPN VXLAN. The diagram below is an example of the topology of MPLS.

The MPLS network is similar to MP-BGP EVPN VXLAN because it is also meant to support multiple L3VNI or L3 overlay service, multi-tenancy in short. The MPLS Provider (P) routers that perform label switching is similar to the VXLAN underlay that routes traffic between VTEPs based on the outer IP headers. The MPLS Provider Edge (PE) routers are similar to the VTEPs such that they participate in MP-BGP control plane and they are responsible for interfacing between the underlay and the consumers. The MPLS Customer Edge (CE) are similar to the consumers (a.k.a host) as they need to be isolated from other organization.

The MPLS network that is a shared medium that will be used by multiple independent organisations to route traffic between each other. For scalability, the MPLS network will use a single BGP instance to exchange prefixes between sites. Route Distinguisher (RD) will be used to ensure IP addresses are non-overlapping. MP-BGP VPNv4 will be used to exchange the prefixes between PE routers. Route Targets (RT) will be used to ensure that the PE import and export to organisation VRF, only the prefixes that belongs to a that organisation.

With the above understanding, we will find that MP-BGP EVPN VXLAN employs similar concept, and more.

Purpose of VRF in EVPN Fabric for L3 Overlay

To understand how routing works in a MP-BGP EVPN VXLAN, we need to first understand the purpose of Virtual Routing and Forwarding (VRF) in the fabric. The next generation data center fabric is built with multi-tenancy in mind. The data center could be serving multiple customers, or their sub-organization could require isolation between their workloads and traffic. VRF is used in the networking infrastructure to support segmentation at a macro level.

Why is VRF Configuration Required for Intra-VRF Communication?

Well, the short-answer I believe is the use of overlay technologies. As the next-gen data center and MP-BGP EVPN is designed with multi-tenancy in mind, even for a lab environment with only 1 tenant (a.k.a 1 VRF), the configuration still need to include 1 VRF. Not forgetting that there is an underlay in a the fabric as what we have discussed in previous blog post. The separation of overlay (VRF) and underlay (GRT) routes further necessitates the presence of VRF even when there is only 1 tenant.

Why is EVPN Insufficient as Control Plane for Routing?

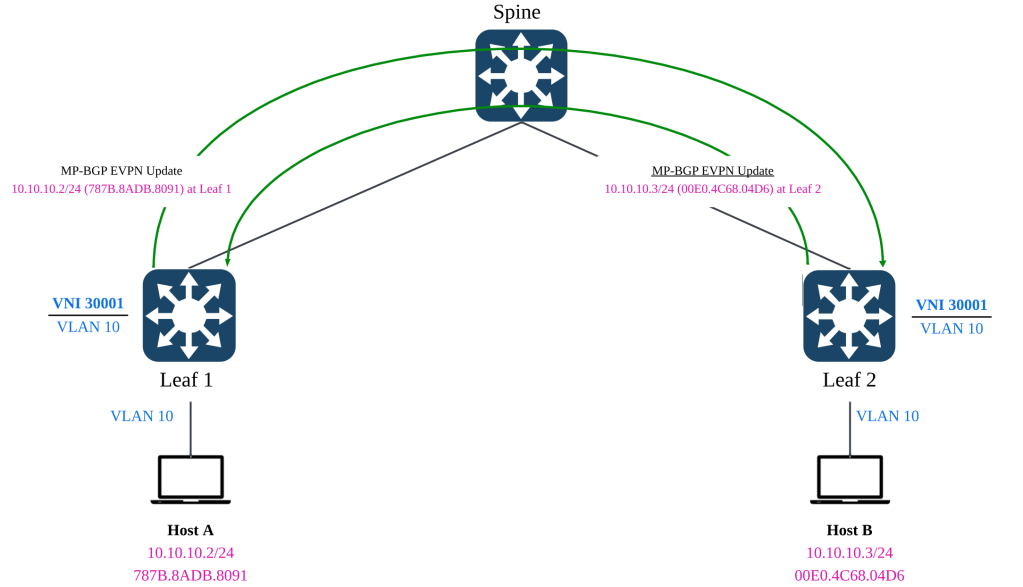

In the previous blog post in which we have discussed bridging using L2VNI, we have leveraged on MP-BGP EVPN address family. With EVPN supporting optional IP prefixes, VTEPs in the fabric are able to learn the MAC and IP bindings of the hosts, and the remote VTEPs that its located.

For routing between different L2VNIs or subnets, we will not able to rely solely on EVPN. Although, EVPN can carry both MAC address, MAC address with IPv4 address and IPv4 subnet routes (Type-5), this is insufficient from a routing standpoint.

Routing Policy & Control

In layer 3 routing, there will be instances whereby injecting a default route to external gateway is required, or to control the leaking of routes between VRFs via route import & exports and manipulation of next hops via Policy Based Routing (PBR). These capabilities are not support by the limited optional L3 attributes in EVPN. Furthermore, since the L3 attributes (E.G Type 5 network routes) is optional, routing cannot depend on it being optional.

Support for Multi-Tenancy

As mentioned earlier, the use of VRF even for a single L3VNI is required because the solution is built with multi-tenancy in mind. The presence of overlay and underlay signals the need for routing separation between underlay (GRT) and overlay (VRF). With multiple L3VNI (VRF) in play, the MP-BGP control plane must be capable of advertising the host and network routes in isolation from the other L3VNIs (VRF).

Although EVPN is able to carry the L3VNI tag in its advertisement, EVPN is not able to support key L3 capabilities such as prefix exchange, route leaking and external connectivity with multi-tenancy (VRFs) in mind. The L3VNI tag in EVPN advertisement is only to signal which VNI to be used for routing when bridging is insufficient.

Lab of the Day (LOOD)

In the lab work today, we will be setting up routing between host A and host B that resides in different L2VNI, but within the same L3VNI. In layman terms, this will be inter-subnet routing in the same VRF.

Both leaf 1 and leaf 2 will be configured with the Distributed Anycast Gateway (DAG) to support Layer 3 routing. Essentially the end goal is to allow both hosts to have reachability to each other using the L3VNI. As this scenario is not designed to test the mobility of the host, we will not be aligning the MAC address of the default gateways yet.

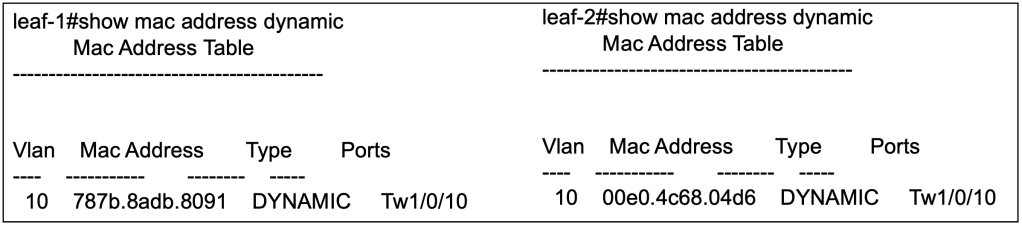

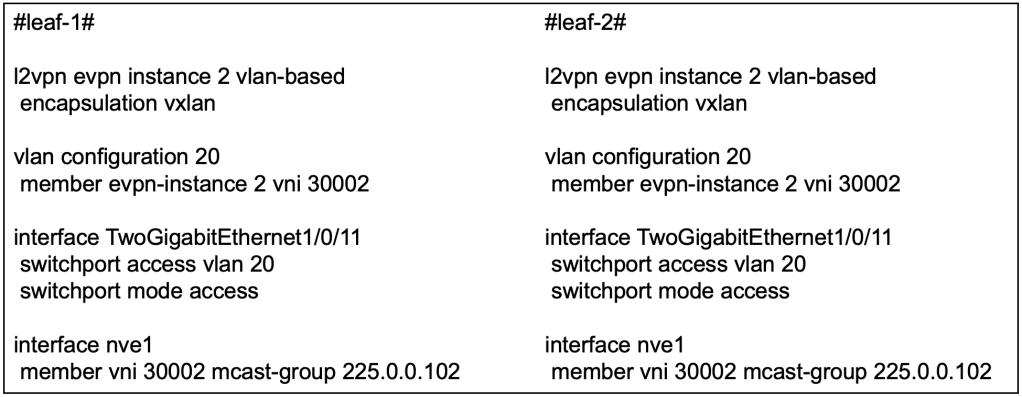

L2VNI Preparation

Before we proceed with the most interesting part of today’s topic, we must make sure that we have the L2VNIs setup in both switches. Technically, we only require one unique L2VNI per switch but since we continuing on from previous lab, we already have L2VNI 30001 configured on both switches in the previous article. We shall proceed to configure L2VNI 30002 on both switches as well.

At this point, if host A and host B are connected to Tw1/0/11, they will be able to reach each other using L2VNI 30002.

L3VNI Preparation

VRF Definition

The first activity we need to do is to create a new VRF to represent the L3 overlay service, L3VNI. In this example, we will use VRF red.

We have also defined the Route Distinguisher (RD) to be used in conjuncture with the VRF. RD unlike route target, has a subtle use case. In a multi-VRF environment where overlapping IP addresses may occur, RD provides unique-ness to the address. Hence, both leaf can use the same RD for the same VRF because they will not have overlapping IP address.

In subsequent articles where we dive into multi-tenancy or access to shared services, we will revisit this sub-topic and each VRF will require their own distinct RD.

L3VNI Definition

Next, we will create a new VLAN to associate to a L3VNI.

In this example, we will create a dummy VLAN 500 and associate it L3VNI 50001. With this config alone, there is still no indication that the VNI is L3.

We will then create an SVI for the VLAN 500. This SVI will have no IP address and will be assigned the VRF (red) to be used. Essentially, this SVI will be used for routing between the VTEPs.

The command no autostate is required because there will not be any access or trunk ports associated with this SVI. Without the command, this interface will go down.

Distributed Anycast Gateway (DAG)

Now let’s move into the section on configuring the default gateway for L2VNI 30001 and L2VNI 30002. Because the lab is on routing between subnets / L2VNIs, we will need to provide default gateways for the subnets.

In both leaf, because we are using DAG, the IP address on both SVI will be the same. We will also put them in the same VRF (red) so that routing between the subnets will traverse over the same L3 overlay (L3VNI).

Because in the current lab scenario, we are testing routing between hosts on different subnet, we do not require to configure the same default gateway MAC address on the VTEPs. We will need to configure the same default-gateway MAC address on the VTEPs when we test endpoint mobility between the leaf switches. We will leave that for the later section. So at this point, this is still not fully a DAG yet.

Enabling L3VNI on NVE

On the Network Virtualization Edge (NVE), apart from the existing L2VNI association, we will need to associate the L3VNI with the VRF.

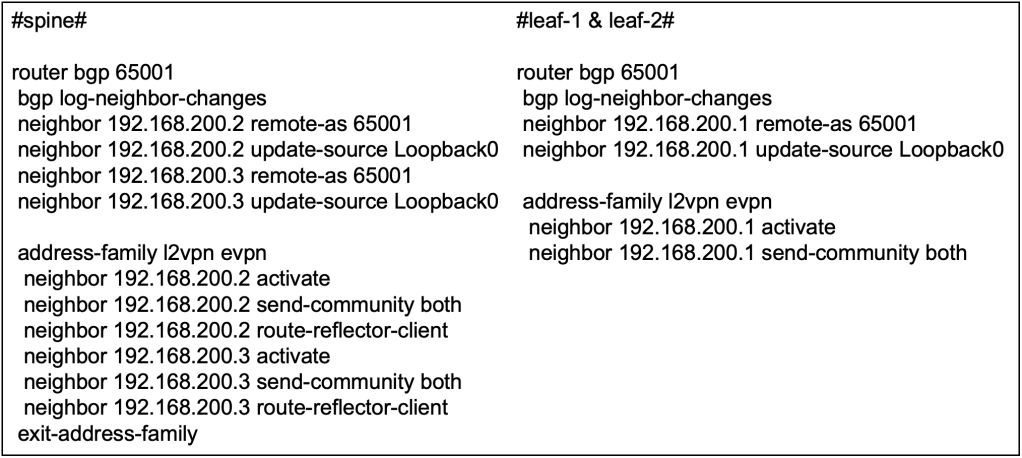

MP-BGP IPv4 Unicast for L3 Overlay Control Plane

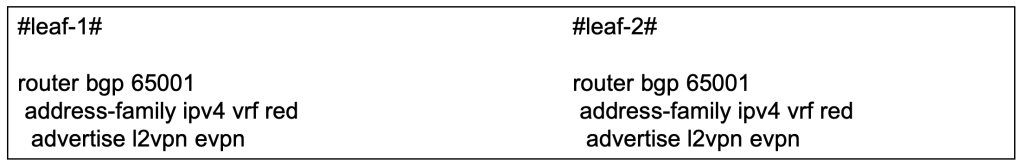

As discussed in the initial section, we will require the use of IPv4 unicast address-family in BGP to advertise L3 reachability in the fabric because EVPN is mainly used for L2 bridging. In this section, we will be configuring the additional IPv4 unicast address family in the MP-BGP.

The reachability information is originally sourced from the EVPN protocol, hence we will need to advertise the EVPN information into the BGP IPv4 address family to be used in L3.

Route Target Import & Export

In the context of multi-tenancy where multiple L3VNI will exist, the VTEP which will be shared among the L3VNIs will need a way to isolate the routes received from BGP. Apart from isolating the routes, we may also need some mechanism to leak the routes between VRFs at the VTEP. We can do so using Route Targets.

In our configuration above, you might find that both leaf-1 and leaf-2 are both importing and exporting the same RT via the VRF IPv4 address family. This is only the case when we only have a single overlay VRF.

Both VTEP are configured to export its prefixes with the RT of 10:10, and to receive prefixes with the RT of 10:10. This means that the prefixes exported by both VTEP, for VRF red, will all be received by the opposing VTEP. We’re trying to make a simple topology here, hence no fuss on the import and export route targets.

However, you might notice that there is a key word “stitching” on import and exports. Why is that so? Let’s move on to the next section.

Stitching RTs for L2VNI and L3VNI

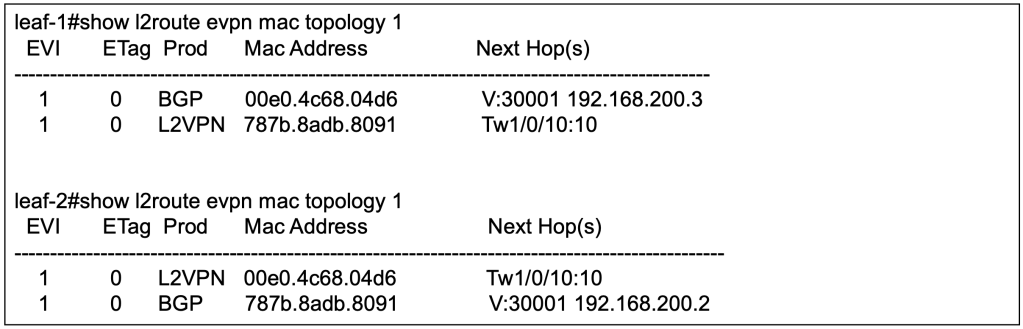

We may often forget that L3VNI and L2VNI have their own respective route targets. Earlier, we have configured to import the VRF to import routes based on RT 10:10. The RT 10:10 was exported under address-family IPv4. However, the EVPN prefixes are not configured with RT 10:10, hence they are not imported yet.

In our example, we have not configured the RT for our L2VNI (30001) and L2VNI (30002). Hence they will use the default format of ASN:EVI, hence it will be 65001:1 and 65001:2.

This is important because when we advertise L2VPN EVPN via the BGP IPv4 unicast address-family for VRF (red), the BGP protocol is taking the learnings from the EVPN and into the IPv4 unicast address-family. Assuming the EVPN information, now riding on IPv4 unicast address-family reaches the destination VTEP, it is up to the VTEP to decide if it will import the prefixes. Hence, this means that the VRF definition on the VTEP needs to import the RT of the L2VNIs that are part of the L3VNI (VRF).

Without importing the EVPN prefixes from the L2VNIs, we will not be able to support inter-subnet, intra-VRF routing because our local VTEP will not be able to learn which hosts or which subnet are residing behind which remote VTEPs.

In NX-OS configuration, we can configure specifically which L2VNI RT to import for a specific VRF. However, for IOS-XE, there is no such command. Instead, stitching is used to import all related L2VNI’s RT within a specific L3VNI.

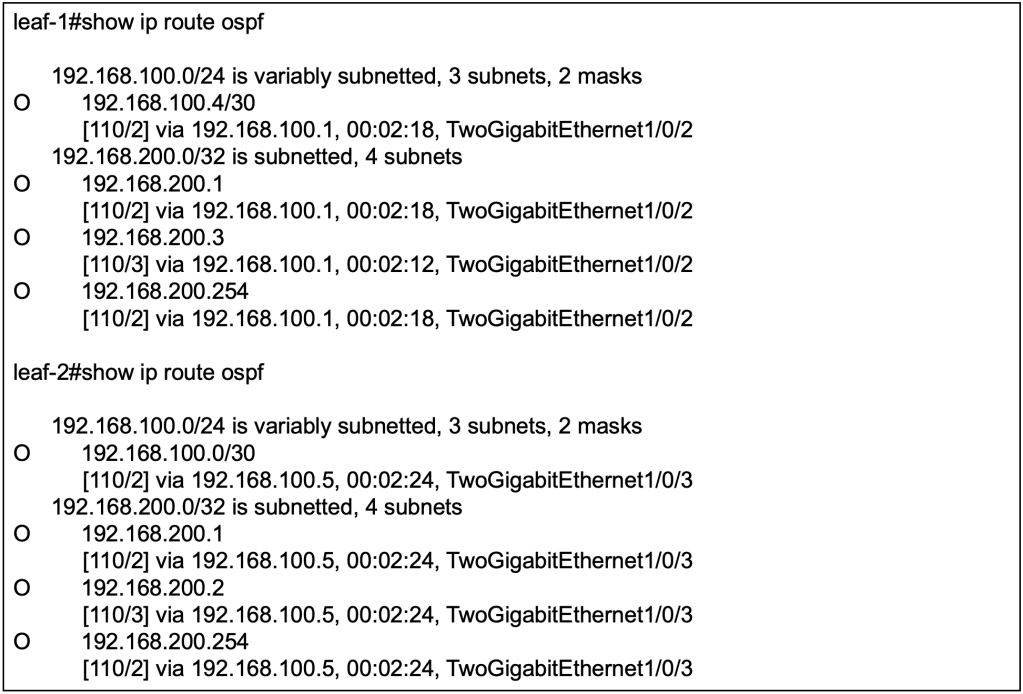

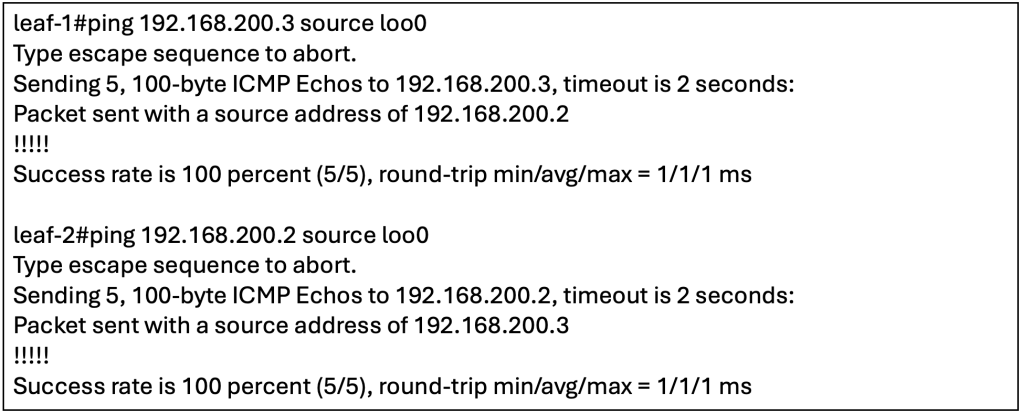

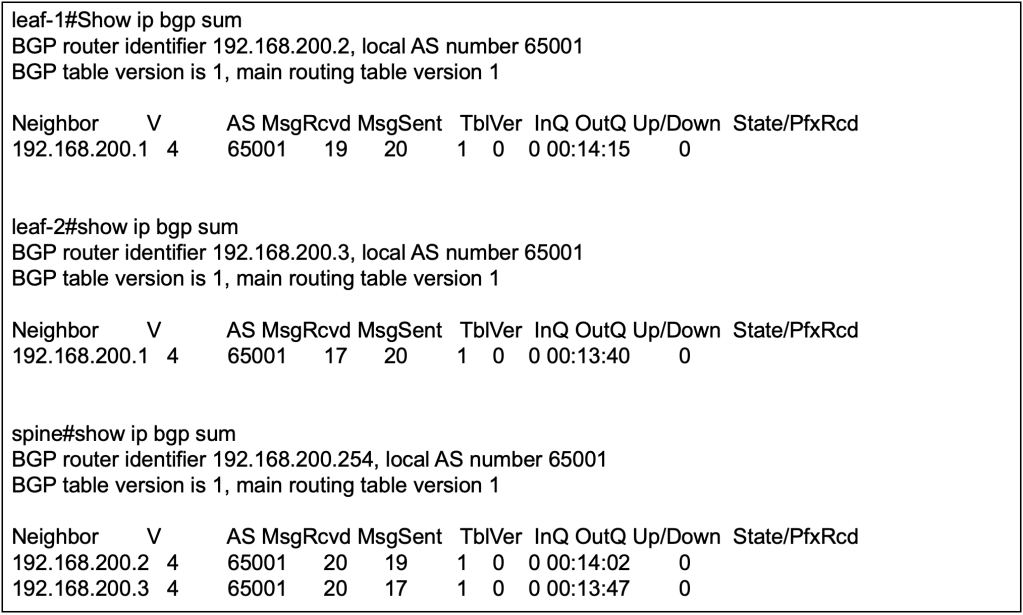

Verification of MP-BGP & RIB

Show ip bgp l2vpn evpn detail

Leaf 1’s BGP EVPN has learnt the IP & MAC binding of the host B behind leaf 2.

By reviewing the detailed output of the BGP L2VPN EVPN, we can observe that the type-2 EVPN prefixes contain the L2VNI & L3VNI and the RT of the L2VNI & L3VNI. The BGP’s IPv4 unicast address family will advertise the EVPN prefixes into its unicast address-family updates.

When the BGP updates reaches the VTEPs, the leaf switches will need to decide which of the L2 (EVPN) and L3 (unicast) information to import to its VRF. This is where the RT of L2VNI and L3VNI is important because over at the VRF definition, we will configure which RT to import for unicast prefixes, and to stitch all the EVPN prefixes from all L2VNI associated to the L3VNI (VRF).

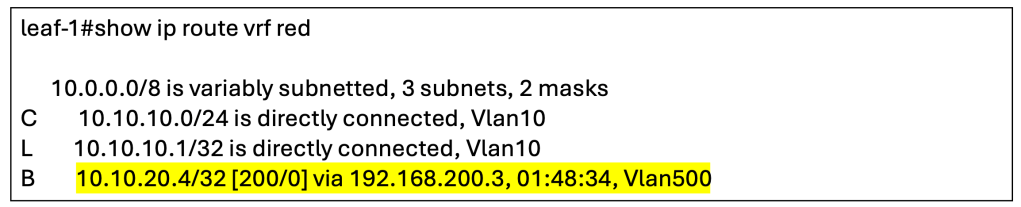

show ip route vrf red

The output has shown that the host route for host B has been installed into the RIB.

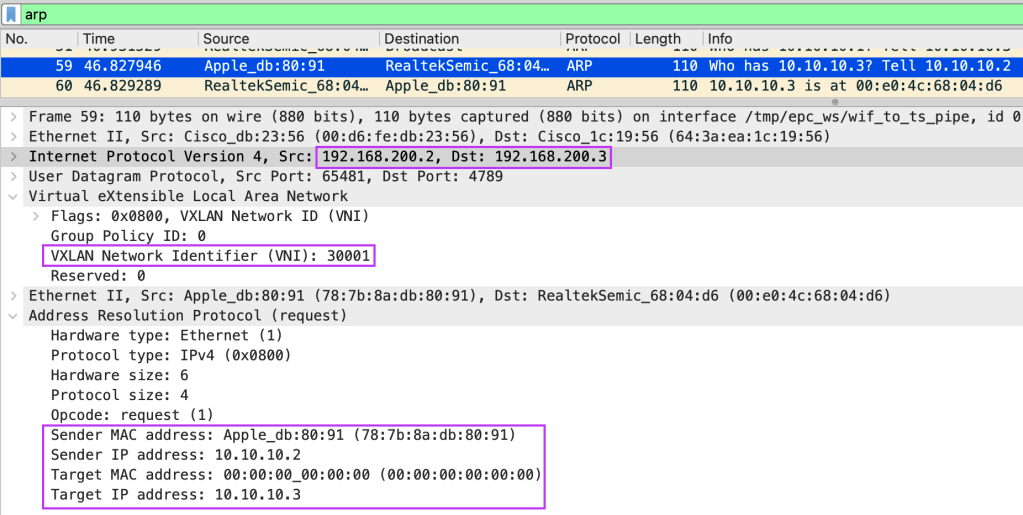

Wireshark Verification

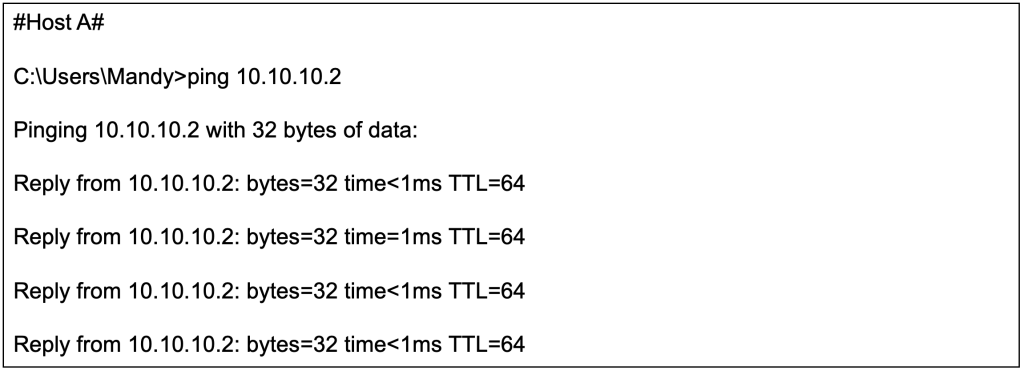

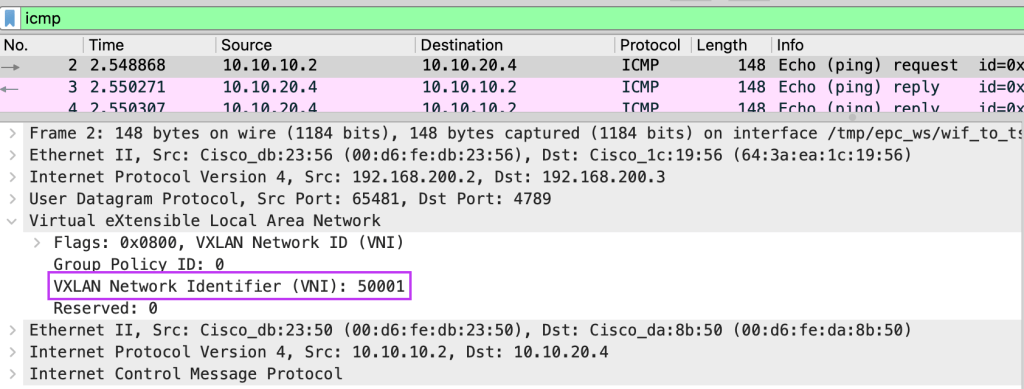

We will now initiate a ping from host A (10.10.10.2/24) to host B (10.10.20.4/24).

We will perform a packet capture on the spine switch to observe the ICMP echo request coming from host A.

From Wireshark, we can observe that the ICMP echo request between different subnets will use the L3VNI (50001) as both host A and host B are still in the same L3VNI, VRF.

Closing Thoughts

This has been a really long topic to learn and write. For sure we have only breach the surface on L3 overlays, but we had a pretty good run in exploring the technology. I hope you have like the articles thus far, next-up we will venture into external connectivity.

Tang Sing Yuen, Cisco Solutions Engineer